Scientific discoveries not applicable in the clinic are a #1 fear of many biomedical researchers. In fact, a harsh reality is that almost 95% of drugs being tested fail in human trials (1). However, there is a ray of hope. In a recent report from Cell magazine, a study shows that propionic acid improves clinical parameters in multiple sclerosis patients (2). Propionic acid, along with acetic and butyric acids, is a major short-chain fatty acid (SCFA), a metabolite derived from the digestion of dietary fibers. Over the last decade, the scientific community reached a consensus that SCFAs can dampen inflammatory responses in pre-clinical settings. Yet, taught by a high failure rate in clinical trials, many are sceptical about the therapeutic value of “postbiotics” (bacterial metabolites that provide health benefits to the host). Now, it is clear that SCFAs deserve our full attention, which is why it is time to tell their story. So, sit back and relax, as we walk you through the winding road of immunology behind these fascinating metabolites.

A brief history

SCFAs induce Treg differentiation

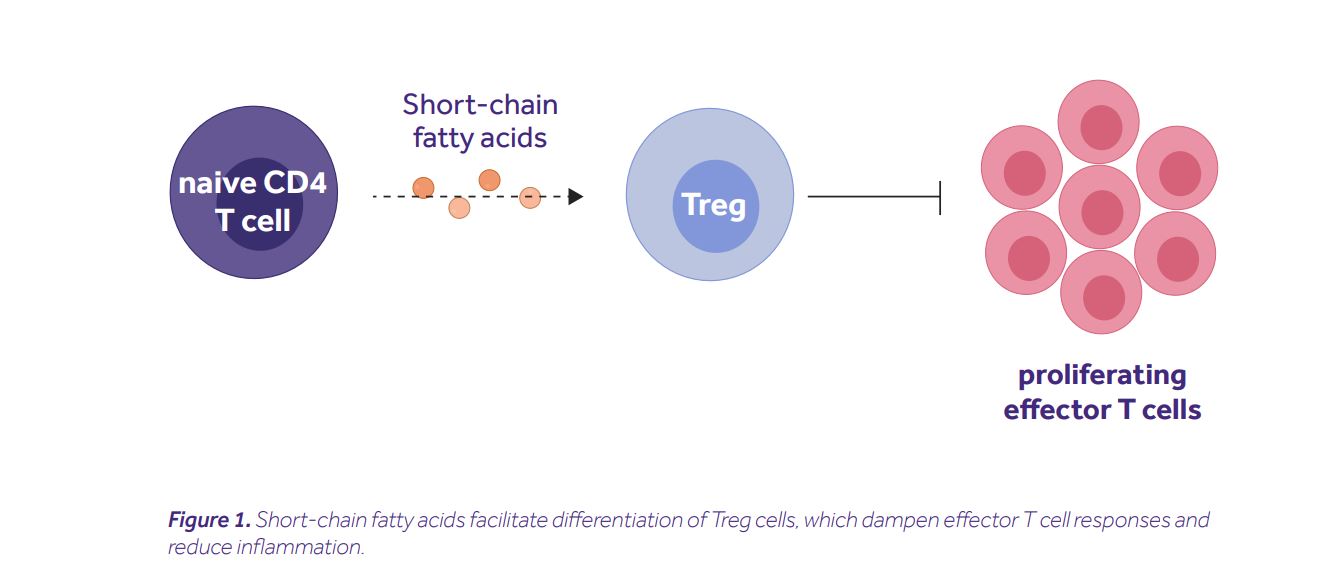

Arpaia and his colleagues started with a simple question: are SCFAs acting directly on naive CD4+ T cells? To answer it, they differentiated naive CD4+ T cells into a Treg subset in vitro, in the presence of increasing concentrations of butyrate. Interestingly, this led to a dose-dependent increase in the frequency of differentiated Tregs, along with the stabilization of FoxP3, their master transcription factor (6). This finding was confirmed and extended by Furusawa et al., who identified detailed epigenetic signatures linked to FoxP3 stabilization. They noted histone H3 acetylation at the promoter site and at the intragenic enhancer element 3 of Foxp3 gene locus, occurring one day prior to Foxp3 expression (7). Finally, Smith and his colleagues recapitulated these observations using propionate, which inhibited histone deacetylation (thus, increased histone acetylation), and contributed to a higher expression of FoxP3 in colonic Tregs. Importantly, those Tregs were more efficient at suppressing effector T cell responses than Tregs from water-treated controls (8). It is important to note that the described mechanism is not exclusive. Several other groups showed the capacity of SCFAs to mediate anti-inflammatory effects in Treg-independent ways, e.g. via modulation of a dendritic cell function (9), alteration of hematopoiesis in the bone marrow (10), or activation of inflammasome (11).

Although these observations were fascinating on their own, what truly inspired us to share this story were the recent findings from the aforementioned human study by Duscha et al.

It is important to note that the described mechanism is not exclusive. Several other groups showed the capacity of SCFAs to mediate anti-inflammatory effects in Treg-independent ways, e.g. via modulation of a dendritic cell function (9), alteration of hematopoiesis in the bone marrow (10), or activation of inflammasome (11).

Although these observations were fascinating on their own, what truly inspired us to share this story were the recent findings from the aforementioned human study by Duscha et al.

SCFAs in multiple sclerosis patients

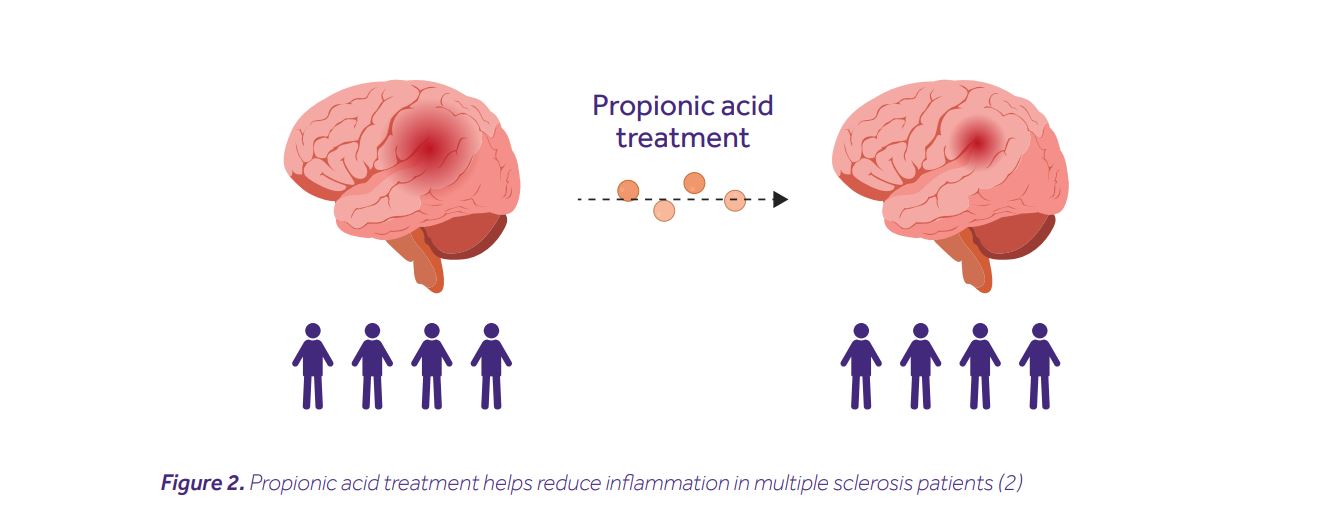

It all started with a simple question: do SCFA levels vary between healthy individuals and MS patients? In the quest for an answer, Duscha and his colleagues recruited two multiple sclerosis cohorts (made up of 268 and 36 patients respectively), and a healthy control cohort (of 68 individuals). They then measured their SCFA concentrations from serum and stool samples. Although no differences in the levels of butyric or acetic acids were noted, MS patients from both cohorts had significantly lower levels of propionic acid (PA). This was accompanied by differences in their microbiota composition, e.g. depletion of SCFA-producing Butyricimonas, and an increase of Flavonifractor, Escherichia, Shigella and Collinsella. MS patients are known to have imbalanced T helper cell responses, i.e. increased frequencies of pathogenic Th17 cells and decreased frequencies of anti-inflammatory Tregs. This gave the researchers the rationale to hypothesize that PA treatment may restore this imbalance and improve a disease course. Indeed, PA treatment increased the frequency of Tregs in the blood, restored their mitochondrial respiration, elevated secretion of interleukin-10, and collectively improved the capacity to suppress effector immune responses. Most remarkably, however, patients receiving a prolonged PA treatment (>1 year) had a reduced annual relapse rate, along with a lower risk of disease progression and brain atrophy (Fig. 2).

The take-home message

At the end of the day, the question is, how can these findings be applied to improve the quality of a patient’s life? This study opens doors to various possibilities. First, testing different regimens of PA treatment (dosage, time of administration, route), combined with standard therapies, will be pivotal to maximize therapeutic benefits. Second, exploring the prophylactic potential of PA treatment in individuals at risk for MS development will be invaluable to prevent or delay the disease onset (here again, various regimens will have to be tested). All of these studies will have to be performed in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials to draw definitive conclusions. The study conducted by Duscha et al. presents a proof of concept for the clinical benefits of postbiotics. This may seem like a small step, but after all, such are most first steps.Bibliography

[1] Seyhan AA, Carini C. Are innovation and new technologies in precision medicine paving a new era in patients centric care? J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):114.

[2] Duscha A, Gisevius B, Hirschberg S, Yissachar N, Stangl GI, Eilers E, et al. Propionic Acid Shapes the Multiple Sclerosis Disease Course by an Immunomodulatory Mechanism. Cell. 2020;180(6):1067-80 e16.

[3] Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, Kranich J, Sierro F, Yu D, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461(7268):1282-6.

[4] Le Poul E, Loison C, Struyf S, Springael JY, Lannoy V, Decobecq ME, et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(28):25481-9.

[5] Fukuda S, Toh H, Hase K, Oshima K, Nakanishi Y, Yoshimura K, et al. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature. 2011;469(7331):543-7.

[6] Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504(7480):451-5.

[7] Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446-50.

[8] Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341(6145):569-73.

[9] Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, Sichelstiel AK, Sprenger N, Ngom-Bru C, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med. 2014;20(2):159-66.

[10] Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Pattaroni C, Lopez-Mejia IC, Riva E, Pernot J, et al. Dietary Fiber Confers Protection against Flu by Shaping Ly6c(-) Patrolling Monocyte Hematopoiesis and CD8(+) T Cell Metabolism. Immunity. 2018;48(5):992-1005 e8.

[11] Macia L, Tan J, Vieira AT, Leach K, Stanley D, Luong S, et al. Metabolite-sensing receptors GPR43 and GPR109A facilitate dietary fibre-induced gut homeostasis through regulation of the inflammasome. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6734.