In our previous blog post, we described a possible cellular source to generate “universal” donor cells for off-the shelf application in cancer immunotherapy. We are following our discussion on this topic with unconventional subsets of T cells that do not require extensive genome editing for safe administration. In particular, we will focus on a unique gamma delta T cell (γδ T cell) subpopulation that has received a lot of attention in cancer immunotherapy over the past decade. [1, 2]

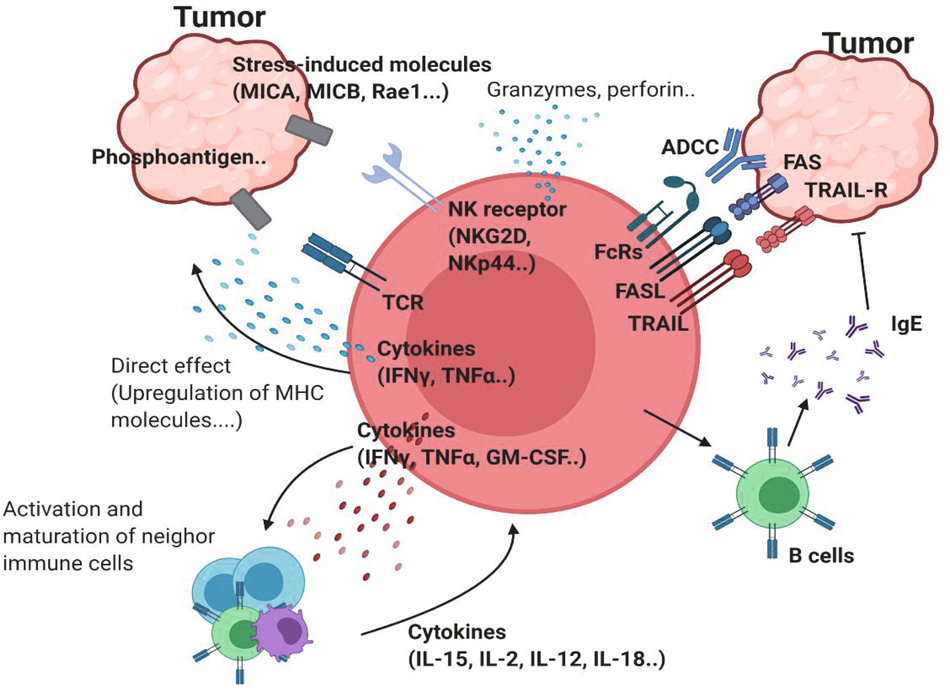

γδ T cells are a distinct subgroup of T cells that contain T cell receptors (TCRs) made of one γ chain and one δ chain with diverse structural and functional heterogeneity. γδ T cells are classified in between the adaptive and the innate immune system, as they exhibit a faster immune response compared to αβ T cells. [3] γδ T cells are considered cytotoxic, anti-tumor lymphocytes with a high capacity of IFNγ and TNFα cytokines secretion (Fig. 1). Several characteristics make these cells attractive candidates for cancer immunotherapy. In contrast to conventional αβ T cells, their activation does not rely on the recognition of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-dependent antigen presentation, which allow them to be easily transferred between individuals in an allogeneic setting without the risk of causing Graft vs Host Disease (GvHD). The use of MHC-independent γδ T cells might be particularly effective against antigen-negative or MHC-low tumor cells. Moreover, extensive use of semi-invariant or invariant γ and δ chains that dominate their unique TCR repertoire can be broadly applicable in TCR-based allogeneic cell transfer. Their sensing of cancer cells depends on more ubiquitous changes observed across many individuals, as their molecular targets are expressed on a wide variety of tumor transformed cells.[1] In addition, γδ T cells express CD16 and participate in inducing antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.[4] Lastly, their pattern of cytokine secretion may present a lower risk of cytokine release syndrome.

Here, we will briefly summarize the stage of preclinical and clinical development and discuss opportunities and challenges that these types of cells can offer for off-the-shelf products for cancer therapies.

Figure 1. Antitumor properties of γδ T cells.

γδTCR ligands such as phosphoantigens can bind to γδTCR. Stress-induced molecules, including MICA/B and Rae-1, can bind to NK receptors such as NKG2D. This ligation induces activation of antitumor γδ T cells. Proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFNγ and TNF, can further activate antitumor immunity by inducing MHC molecules on the tumor cell surface or by affecting other immune cells. The upregulation of cytotoxic molecules such as granzymes and perforin can directly kill tumor cells. In addition to these receptors, FcR-mediated ADCC, FAS-FASL, and TRAIL ligation can also induce direct cytotoxicity against tumor cells. γδ T cells can promote B cells to produce IgE, which has an antitumor effect.

Fig. 1: Network of antitumor γδ T cells. | Experimental & Molecular Medicine (nature.com))

Translating γδ T cells into cancer cell therapies

High frequencies of intratumoral γδ T cells represent one of the most favorable prognostic markers in different cancers. Using the cell- type identification by estimating relative subsets of known RNA transcript (CIBERSORT) algorithms, an extensive analysis of immune subset transcriptomic signatures from 18,000 tumors revealed that γδ T cells are the immune subset most significantly associated with a favorable prognosis.[5] Human γδ T cells are broadly divided into two main Vδ1 and Vδ2 subsets based on their TCRδ-chain expression.[3] The potential of γδTCR diversity is however thought to surpass the diversity of αβTCRs. The semi-invariant Vγ9Vδ2 T cells that dominate the γδ T cells in peripheral blood are common targets for γδ T cell-based immunotherapies. Other clones perceived as non-Vγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells comprise a plethora of unique rearrangements of Vδ1 and Vδ3,4,5,6,7,8 pairings with diverse TRG segments (Vγ2,3,4,5,8, and non-invariant Vγ9) that can adopt highly individual forms of immune surveillance.[6-8] The polyclonal repertoire of non-Vγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells which most likely target different ligands would result in diverse and difficult to control off-the shelf products. On the other hand, their wide repertoire may have applications for next generation personalized cancer care. In homeostatic condition, Vδ2 T cells are mainly enriched in the peripheral blood where they represent about 1-5% of all circulating T cells and recognize specifically microbial or stress- or tumor-induced phosphoantigens (PhAgs).[9] In recent years, different and robust protocols have been established to activate and expand both Vδ1 and Vδ2 T cell subsets from peripheral blood, thus, allowing the acquisition of sufficient numbers of cells for utilization in clinical settings.[10, 11] The PhAgs-reactive Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are relatively easier to expand than Vδ1 T cells, due the combinatorial use of both IL-2 and aminobisphosphonates like zoledronate (ZOL), which are able to induce Vγ9Vδ2 T cell expansion in vitro or in vivo by systemic administration of ZOL (Fig. 2).

While the safety of γδ T cell activation in patients has been proven, and the pharmacodynamics of PhAgs administered to humans has been established, the results from these studies have been disappointing.[12-16] The activation and adoptive transfer of expanded in vitro Vγ9Vδ2 T cells was shown to be safe; but also failed.[17, 18] Thus, several aspects still need to be considered carefully. For instance, which ‘variant’ of PhAgs constitutes the major natural biologically active molecule remains to be determined. In alternative, a novel strategy for in vivo activation of tumor-reactive Vδ2 T cells is the therapeutic application of a humanized anti-BTN3A1 mAb.[19] In fact, a clinical trial with such an antibody (ICT01) has just been started (NCT04243499).

On the other hand, hypoxia and chemotherapy also render γδ T cells fragile.[20, 21] Moreover, targeting coinhibitory/stimulatory molecules also might be a good strategy for reinvigorating γδ T cells. For example, anti-CTLA4 antibody treatment increased the frequency of Vδ2 T cells in melanoma patients.[22] Notably, recently widespread expression of the NKG2A checkpoint in human Vδ2 T cells was also demonstrated.[23] On the basis of these new evidences, several new clinical trials are currently ongoing in both solid tumors including breast (NCT03183206, NCT02781805), lung (NCT03183232), liver (NCT03183219), pancreatic (NCT03180437) and bladder (NCT02753309) cancers, and hematological tumors (NCT03533816, NTR6541).[2] In addition, different therapeutic strategies to treat cancers with γδ T cells or extracted receptors from γδ T cells have been developed, through both academic and commercial partners in the field. These approaches are based on the principle of either recruiting available γδ T cells with approved drugs or overcoming polarization towards a tolerogenic profile by inducing the expression of activating molecules through defined in vitro stimulation methods followed by adoptive transfer.

Alternatively, genetic engineering of γδ T cells or the expression of defined tumor- reactive γδTCRs on the surface of αβ T cells are explored in order to overcome the functional constraints linked to γδ T cells (Fig. 2). αβ T cells transduced with γδTCRs (TEGs), enable selecting for the Vγ9Vδ2 TCR with the highest affinity, or for non-Vδ2 γδTCRs, and thereby can target a broad range of tumors in the personalized setting. Using Vγ9Vδ2 TCRs TEGs have been shown to target leukemic stem cells and eliminate primary multiple myeloma in a 3D bone marrow model.[24, 25] Interestingly, CD4+ T cells reprogrammed with a defined Vγ9Vδ2 TCR, not only present cytotoxic properties, but also have the ability to mature professional antigen- presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells (DCs).[26] TEGs expressing a high-affinity Vγ9Vδ2 TCR have been manufactured under GMP conditions and a clinical trial exploring their safety and tolerability are currently being used in a phase I clinical trial in patients with relapsed and refractory AML and multiple myeloma (NTR6541).[27]

γδ T cells are also currently being explored as carriers for chimeric antigen receptor (CARs) T cells. Recently, a new protocol to use γδ T lymphocytes as a platform for CAR-T cells was described by Rozenbaum et al.[28] This pre-clinical study demonstrated the ability to effectively transduce and expand γδ T cells with a CAR targeting CD19. γδCAR T cells were effective against CD19+ tumor cell lines, both in vivo and in vitro. Attempts of γδ T cell transduction with CARs have been also reported previously, however, in this work, a head-to-head comparison of the γδCAR T cells to CAR-T cells shows comparable transduction efficacy and in vitro cytotoxicity against CD19 positive targets. On the other hand, their in vivo effect was profound but inferior to that of CAR-T cells, suggesting that the clinical applicability of γδCAR T cells remains to be tested.

Fig. 2. Antitumor therapies using γδ T cells are currently being developed. PBMCs from patients can be expanded under TCR- and cytokine-stimulating conditions. Expanded γδ T cells can kill tumor cells in vitro. Patient-derived cells can be transduced with engineered γδTCR. γδ CAR-T cells have the potential to be used for therapy. γδTCR-transduced αβ T cells (TEGs) are thought to be effective therapeutic agents. Injection of antibodies against costimulatory molecules or anti-inhibitory molecules can be used to reinvigorate γδ T cells. Reagents, such as zoledronate, can be used to activate γδ T cells de novo.

(From Park, J.H., and Lee, H.K. (2021). Function of gammadelta T cells in tumor immunology and their application to cancer therapy. Exp Mol Med 53, 318-327; Fig. 2: Clinical implication of using γδ T cells. | Experimental & Molecular Medicine (nature.com)

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells can also be redirected against tumor cells with bispecific antibodies (BITEs). In this regard, the (HER2)2xCD16 BITE has been used to redirect CD16+ Vγ9Vδ2 T cells against Her2+ tumor cells that were killed with very high efficiency.[29]

Taken together, there are various strategies available for the in vivo activation and targeting of γδ T cells and for the adoptive transfer of in vitro expanded γδ T cells. This opens up the perspective in the development of γδ T cell-based allogeneic “off the shelf” products that can be manufactured and stored until required for immunotherapy. Support for this idea is evident from the growing interest of several companies that are pursuing this strategy by exploring and optimizing the immunotherapeutic potential of γδ T cells.[30]

References:

- Boyiadzis MM, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T therapies for the treatment of hematologic malignancies: clinical perspective and significance. J Immunother Cancer. 2018 Dec 4;6(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0460-5. PMID: 30514386; PMCID: PMC6278156.

- Martínez Bedoya D, et al. Allogeneic CAR T Cells: An Alternative to Overcome Challenges of CAR T Cell Therapy in Glioblastoma. Front Immunol. 2021 Mar 3;12:640082. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.640082. PMID: 33746981; PMCID: PMC7966522.

- Poirot L, Philip B, et al. Multiplex genome-edited T-cell manufacturing platform for “off-the-shelf” adoptive T-cell immunotherapies. Cancer Res. 2015;75(18):3853–64.

- Valton J, et al. A Multidrug-resistant Engineered CAR T Cell for Allogeneic Combination Immunotherapy. Mol Ther. 2015 Sep;23(9):1507-18. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.104. Epub 2015 Jun 10. PMID: 26061646; PMCID: PMC4817890.

- Qasim W, et al. Molecular remission of infant B-ALL after infusion of universal TALEN gene-edited CAR T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2017 Jan 25;9(374):eaaj2013. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaj2013. Erratum in: Sci Transl Med. 2017 Feb 15;9(377):null. PMID: 28123068.

- Rasaiyaah J, et al. TCRαβ/CD3 disruption enables CD3-specific antileukemic T cell immunotherapy. JCI Insight. 2018 Jul 12;3(13):e99442. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.99442. PMID: 29997304; PMCID: PMC6124532.

- Juillerat A, et al. Straightforward Generation of Ultrapure Off-the-Shelf Allogeneic CAR-T Cells. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020 Jun 25;8:678. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00678. PMID: 32671047; PMCID: PMC7330105.

- Provasi E, et al. Editing T cell specificity towards leukemia by zinc finger nucleases and lentiviral gene transfer. Nat Med. 2012 May;18(5):807-815. doi: 10.1038/nm.2700. PMID: 22466705; PMCID: PMC5019824.

- Torikai H, et al. A foundation for universal T-cell based immunotherapy: T cells engineered to express a CD19-specific chimeric-antigen-receptor and eliminate expression of endogenous TCR. Blood. 2012;119(24):5697–705.

- Torikai H, et al. Toward eliminating HLA class I expression to generate universal cells from allogeneic donors. Blood. 2013;122(8):1341–9.

- MacLeod DT, et al. Integration of a CD19 CAR into the TCR Alpha Chain Locus Streamlines Production of Allogeneic Gene-Edited CAR T Cells. Mol Ther. 2017 Apr 5;25(4):949-961. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.02.005. Epub 2017 Feb 23. PMID: 28237835; PMCID: PMC5383629.

- Hale M, et al. Homology-Directed Recombination for Enhanced Engineering of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2017 Jan 10;4:192-203. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2016.12.008. PMID: 28345004; PMCID: PMC5363294.

- Eyquem J, et al. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature. 2017 Mar 2;543(7643):113-117. doi: 10.1038/nature21405. Epub 2017 Feb 22. PMID: 28225754; PMCID: PMC5558614.

- Ren J, et al. Multiplex Genome Editing to Generate Universal CAR T Cells Resistant to PD1 Inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2017 May 1;23(9):2255-2266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1300. Epub 2016 Nov 4. PMID: 27815355; PMCID: PMC5413401.

- Georgiadis C, et al. Long Terminal Repeat CRISPR-CAR-Coupled “Universal” T Cells Mediate Potent Anti-leukemic Effects. Mol Ther. 2018 May 2;26(5):1215-1227. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.02.025. Epub 2018 Mar 6. PMID: 29605708; PMCID: PMC5993944.

- Ren J, et al. A versatile system for rapid multiplex genome-edited CAR T cell generation. Oncotarget. 2017 Mar 7;8(10):17002-17011. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15218. PMID: 28199983; PMCID: PMC5370017.

- Morgan MA, et al. Use of Cell and Genome Modification Technologies to Generate Improved “Off-the-Shelf” CAR T and CAR NK Cells. Front Immunol. 2020 Aug 7;11:1965. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01965. PMID: 32903482; PMCID: PMC7438733.

- Chakrabarti S, et al. Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) in allogeneic stem cell transplantation: where do we go from here? Transplant Proc. 2004 Jun;36(5):1225-7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.05.067. PMID: 15251298.

- Stadtmauer EA, et al. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science. 2020 Feb 28;367(6481):eaba7365. doi: 10.1126/science.aba7365. Epub 2020 Feb 6. PMID: 32029687.

- Pfefferle A, Huntington ND. You Have Got a Fast CAR: Chimeric Antigen Receptor NK Cells in Cancer Therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Mar 17;12(3):706. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030706. PMID: 32192067; PMCID: PMC7140022.

- Veluchamy JP, et al. The Rise of Allogeneic Natural Killer Cells As a Platform for Cancer Immunotherapy: Recent Innovations and Future Developments. Front Immunol. 2017 May 31;8:631. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00631. PMID: 28620386; PMCID: PMC5450018.

- Shin MH, et al. NK Cell-Based Immunotherapies in Cancer. Immune Netw. 2020 Mar 9;20(2):e14. doi: 10.4110/in.2020.20.e14. PMID: 32395366; PMCID: PMC7192832.

- Liu E, et al. Use of CAR-Transduced Natural Killer Cells in CD19-Positive Lymphoid Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 6;382(6):545-553. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910607. PMID: 32023374; PMCID: PMC7101242.

- Godfrey DI, et al. The burgeoning family of unconventional T cells. Nat Immunol. 2015 Nov;16(11):1114-23. doi: 10.1038/ni.3298. Erratum in: Nat Immunol. 2016 Feb;17(2):214. Erratum in: Nat Immunol. 2016 Apr;17(4):469. PMID: 26482978.

- Tzannou I, et al. Off-the-Shelf Virus-Specific T Cells to Treat BK Virus, Human Herpesvirus 6, Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr Virus, and Adenovirus Infections After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Nov 1;35(31):3547-3557. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.0655. Epub 2017 Aug 7. PMID: 28783452; PMCID: PMC5662844.

- Cruz CR, et al. Infusion of donor-derived CD19-redirected virus-specific T cells for B-cell malignancies relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant: a phase 1 study. Blood. 2013 Oct 24;122(17):2965-73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-506741. Epub 2013 Sep 12. Erratum in: Blood. 2014 May 22;123(21):3364. PMID: 24030379; PMCID: PMC3811171.

- Chapuis AG, et al. T cell receptor gene therapy targeting WT1 prevents acute myeloid leukemia relapse post-transplant. Nat Med. 2019 Jul;25(7):1064-1072. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0472-9. Epub 2019 Jun 24. PMID: 31235963; PMCID: PMC6982533.